Removing installations

Oil installations had to be removed one way or another from fields which were depleted. The first removal project, Brent Spar, ended up as a highly controversial environmental issue. Popular protests revealed the need to develop procedures for removing oil installations through international agreements and national cessation plans.

Fifteen of the 29 installations in the Ekofisk area have been covered by such a plan, with removal of these structures due to be completed in 2016. But the most complete example of a removal project for a whole field on the Norwegian and UK continental shelves is being provided by Frigg between 2004 and 2010.

Brent Spar

The debate on the removal of the Brent Spar installation from the UK sector put the environmental challenges related to terminating petroleum operations seriously on the agenda.

The Brent Spar affair became a symbol which clearly demonstrated the issues raised by decommissioning of petroleum installations. This structure was a floating buoy for storing crude from Britain’s Brent field and loading it into shuttle tankers. After the Brent System oil pipeline to Sullom Voe in Shetland came into use in 1978, the loading buoy was used less and less and the decision to remove it was taken in 1991.

Operator Shell UK assessed various options for dumping or removing the structure. The main alternatives were to sink the installation in deep water or take it to land for melting down or other forms of recycling. Shell UK applied to sink Brent Spar in deep water off the west coast of Scotland on the basis that this was the most environment-friendly solution. Shell UK stated that the concequences would be negligable, after an assessment of safety, environment and costs. The British government approved the sinking in deep waters in 1995.

Nevertheless, the project ran into opposition. Greenpeace headed a campaign to bring the installation to land. The environmentalists claimed that deposition in deep water would cause greater damage than Shell UK had specified as likely. It was alleged that the residual oil in the storage tanks would pollute the ocean environment, and that dumping waste in the sea was wrong in principle as well as harmful. In the aftermath, Greenpeace admitted that they had wrongly stated that Brent Spar contained 5000 tons of oil.

Environmental activists organised a high-profile campaign against the plans, and some of them “occupied” Brent Spar for several weeks in the spring of 1995. These actions attracted big media headlines worldwide. A consumer boycott of Shell products was also organised. A number of European politicians spoke up in support of the activists, and official protests were issued by several countries around the North Sea.

Brent Spar was brought to land in Norway during the summer of 1995, and Shell UK resolved to disassemble it there. The tower was used in 1999 as the foundation for an expansion of the harbour at Mekjarvik near Stavanger.

This affair directed attention at the oil industry’s environmental responsibility, and at the fact that the North Sea business had reached a phase where removing installations occupied an ever larger place.

Greenpeace summarised the campaign over Brent Spar as its greatest success. The oil companies were made fully aware of how damaging massive media coverage could be to their reputation with the general public. Their work with environmental matters were intensified. A number of them launched campaigns to communicate their philosophy on and targets for the environment.

Annual environmental and social reports were issued alongside normal financial reporting. This allowed the companies to convey their thoughts on environmental issues. In its 1998 environmental report, Shell UK wrote that the Brent Spar affair showed that official permission was not enough. Acceptance by various organisations and a broad range of community groups such as fisheries and environment groups was also needed.

The most important lesson for the oil companies was the importance of active dialogue with everyone from governments to environmental organisations. Brent Spar came to symbolise the way a company should not communicate with the outside world. A practice based on cessation plans, including an impact assessment, had since the early 1990ies been developed in Norway for handling offshore decommissioning. This was formalized thorugh the Norwegian Petroleum Act of 1996, which stated that the owners should make a cessation plan consisting of an impact assessment and a plan for disposing of the installations. Since the impact assessment was to be circulated for comment, on a public hearing lasting three months all interested parties would be made aware at an early stage of which installations were due for removal and be given opportunities to influence and comment the content of the assessment.

The Ospar convention

The Oslo-Paris convention for the protection of the marine environment of the north-east Atlantic (Ospar) was established in Paris in 1992. Ratified by Norway and most of the other west European nations, the regional convention came into force on 25 March 1998. The convention was established in 1992 in Paris.

Ospar covers all human activity which could have a negative impact on the maritime environment in the region. Governments have undertaken to do whatever is possible to prevent pollution from sources in this sea area.

The convention has played a key role in issues related to disposing of redundant offshore installations. When petroleum production ceases, the general rule is that the installations must be removed and taken to land. Possible exceptions include concrete gravity base structures (GBSs), particularly heavy steel jackets and damaged installations. Dumping structures in deep water is no longer an option.

This obligation was reiterated in july 1998 through the Sintra declaration of the European Commission. It followed OSPAR Decision 98/3 on the Disposal of Disused Offshore Installations. According to this decision ‘The dumping, and the leaving wholly or partly in place, of disused offshore installations within the maritime area is prohibited.’ The goverment of one of the signatory parties can give permission to leave installations in place, rather than reuse, regaining or disposal onshore. Such a permission can only be given after a comprehensive comparative judgement of the alternatives, and after a consultation process. in accordance with the OSPAR convention. Possible exemptions are concrete bases, heavy steel-jackets and damaged installations.

The UN’s International Maritime Organisation (IMO) has adopted regulations which apply worldwide. Guidelines approved in 1989 specify that jackets standing in less than 75 metres of water and weighing below 4 000 tonnes must be removed after abandonment. These rules were extended in 1998 to waters down to 100 metres for platforms installed from that year. These regulations are superseded by Ospar for Norway and the UK, as the only countries in the convention’s region with installations in waters deeper than 75 metres.

Removal costs

Generally speaking, leaving a platform on the field is the cheapest option for the oil companies and the government – particularly where the support structure is concerned. The most expensive solution is to take the installations to land for re-use or recycling. But this option could be cheaper if part of an installation needs to be cleaned of pollutants, because such work is more resource-intensive.

Efforts have also been made to sell installations for removal and re-use in other contexts. In practice, such sales have been confined to individual components. Most of the materials have been sold as scrap for smelting down.

In Norway, the state covers much of the cost of removing oil installations. This contribution was earlier calculated on the basis of what each licensee had paid in tax and how long it had owned the assets. The government paid a direct grant, so that removal costs could not be deducted from taxable income. After the Act of 1986 was revoked in June 2004, however, such costs are now treated as normal deductions in accordance with Norwegian tax legislation.

Where the state has interests in an oil company or a licence, the government also meets its share of removal costs directly. This means in reality that much of the expense of platform abandonment is covered from the public purse. The cost of removing all installations on the NCS was put in 1995 at NOK 40 billion.

North East Frigg and Odin

The first removal projects in the Norwegian petroleum business involved installations tied back to Frigg, which received petroleum from a series of satellite fields. Structures on North East Frigg and Odin were removed in 1996 and 1997.

Production from North East Frigg, operated by Elf, ceased on 8 May 1993. The contract to remove its installations was awarded to the North East Frigg Abandonment Joint Venture (Nefa). Sinking the control column in deep water was considered during the planning process, but it was taken to land in 1996.

At the suggestion of the project manager, the steel column was installed as a mole for the marina at Tau outside Stavanger with the concrete base used to anchor it. The topside structure was taken over by the North Sea Drilltrainer centre for educating drilling personnel at Tau near Stavanger. After being brought ashore, the subsea template has been scrapped and the materials recycled. One of the wellheads is preserved at the Norwegian Petroleum Museum.

The steel platform on the Odin gas field, operated by Esso, was relatively small. The jacket weighed about 9 000 tonnes. This structure was disassembled and lifted in three sections by the Saipem 7000 crane barge. Shipped to Stord in western Norway during 1996-97, these units represented the first complete production platform to be removed from the NCS.

Operator Esso proposed leaving the jacket on the seabed by overturning it, as a pilot project for the creation of artificial fish reefs. However, the Norwegian government resolved that it should be taken in to land. On the one hand, using the jacket as a reef would attract fish and possibly create a new area for fish growth. But it would also represent a hazard for trawling.

Experience from decommissioning Odin showed that it can often be cheaper to take a jacket to land than to sink such structures in deep water. Transport costs are roughly the same, because the installation has to be moved in any event. Removing pollutants also costs more at sea than on land. In addition, companies risk being held liable for possible future damage related to dumping in deep water.

Maureen and Ekofisk

A major removal project was implemented in 1999-2001 by operator ConocoPhillips on Britain’s Maureen field, involving the big Alpha platform with its steel sub-structure. The latter had been equipped with tanks to re-float it, and the structure was designed for possible removal. That made the operation relatively simple.

The platform was towed to Stord and broken up. Its sub-structure ended up as the foundation for a quay at nearby Leirvik, while the loading buoy with a large quantity of concrete became a breakwater for a marina. Up to 95 per cent of the remaining material was recycled.

Removal is also planned by operator ConocoPhillips for the oldest platforms in the Ekofisk area, which are now redundant. Fifteen of 29 installations are included in the removal plan for Ekofisk I, the first development phase on the field. In consultation with the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, 11 of these structures are due to be removed in 2006-13. The timetable for the remainder will be determined later.

Topsides and steel jackets are being taken to land for recycling. However, permission has been given to leave the concrete Ekofisk tank in place after its superstructure has been removed and the interior thoroughly cleaned. Leaving buried pipelines and drill cuttings has also been authorised.

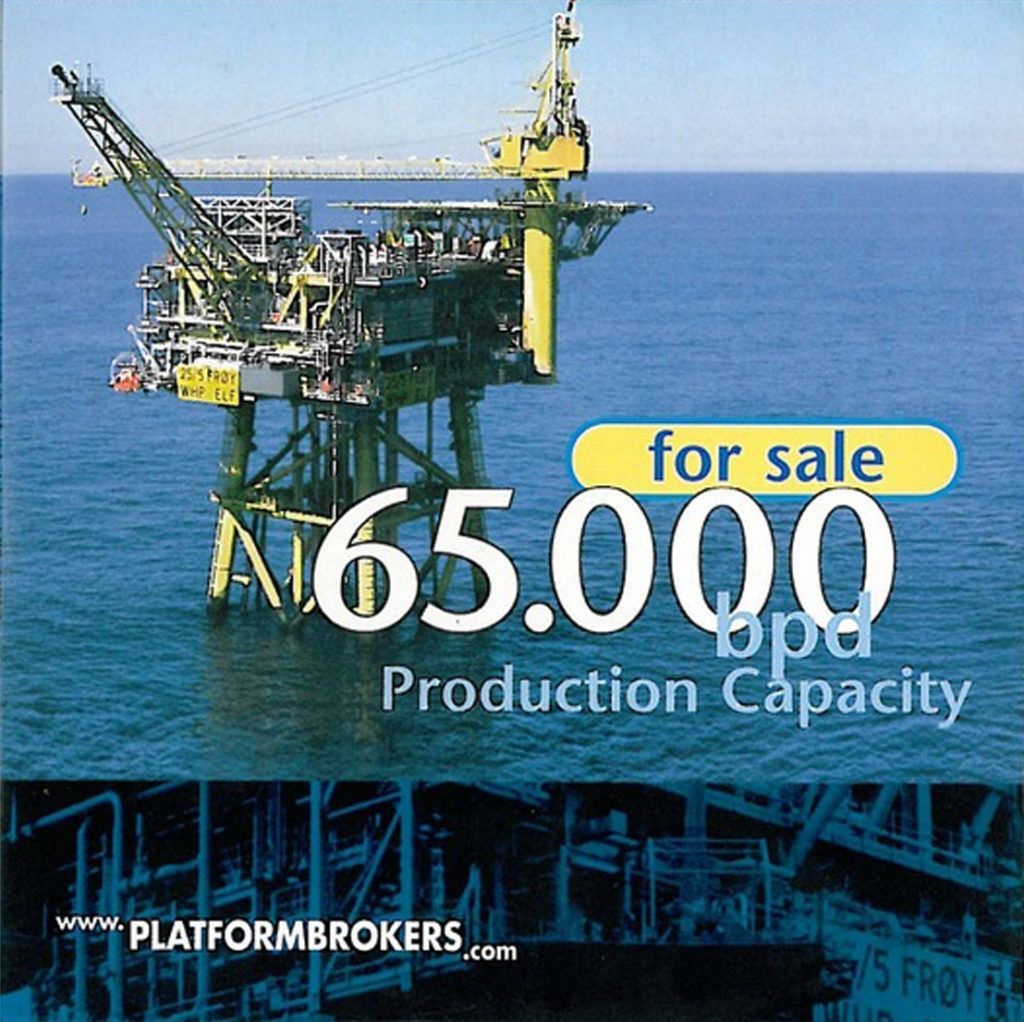

Frøy, Lille-Frigg and East Frigg

Shutting down the Lille-Frigg and Frøy fields in the later 1990s was based on the Ospar convention. Production from these two Frigg satellites had begun to decline, and Elf resolved in 1998 to market their installations for sale. A number of companies had begun to specialise in selling and recycling oil installations, and internet databases were established for marketing such structures.

Lille-Frigg ceased production in March 1999. Removal of the templates was prepared by Coflexip Stena Offshore (CSO) and carried out by SSCV Thialf in July 2001. The latter is the world’s largest semi-submersible crane vessel, able to lift up to 14 200 tonnes with its dual cranes. While the control system and other wellhead components were sold, the actual template was delivered for smelting and recycling.

Frøy ceased to produce on 5 March 2001, after just six years on stream. A sale of the steel jacket for use in the British sector was considered but not carried out. After the shutdown, TotalFinaElf – as the operator was then called – sold the platform to Lyngdal Recycling AS. Heerema Marine Contractors Nederland BV coordinated its removal from the field. Thialf lifted the whole 7 000-tonne jacket from the seabed in one piece and carried it to Mekjarvik for breaking up. The 200-tonne topsides was taken to Lyngdal and stored in anticipation of possible re-use. Lyngdal Recycling disassembled the platform and sold most of the equipment. The rest was recycled.

East Frigg shut down on 22 December 1997 after producing for nine years. The five production wells were plugged during the first half of 1999. Removal of the templates was prepared by CSO and carried out by Thialf in July 2001. Installation tools and Xmas trees were sold and the protective frameworks recycled.

Frigg

The process for approving the cessation plan for the actual Frigg installations got seriously under way in 1999. The operator Total E&P Norge took five years to secure final approval. Pursuant to the Frigg treaty, the British and Norwegian governments agreed that the disposal of all the installations on the field should be outlined in one cessation plan. This would also take account of each nation’s legal requirements, and accord with the principles which had underlain the operation of Frigg throughout.

This comprehensive decision-making process was intended to ensure the participation of all interested parties, both in Norway and the United Kingdom. An extensive process of consultation involved obtaining comments from both fisheries and environmental organisations and government authorities. The plans involved to leave the concrete bases of the platforms, therefore the signatories of the OSPAR-convention also had to be consulted, in accordance to OSPAR decisjon 98/3.

A cessation plan for Frigg was submitted to the UK and Norwegian authorities in November 2001, and was on public hearing for three months. The principles for shutting down and removal had to be approved by both governments. During the process, weight was given to maintaining close contact with and securing comments from various stakeholders. These included environmental and fishing organisations as well as government agencies. The process was pursued in such detail to avoid the kind of confrontations associated with Brent Spar.

In 2003 it was decided that the platform MCP-01 in british sector should be taken out of use. The MCP-01 had a concrete base, and was part of the pipeline system to the gas terminal at St Fergus in Scotland. The operator Total E&P UK in Aberdeen decided that the removal of the topsides at MCP-01 should be a part of the Frigg cessation project, with Total E&P Norge in charge. In 1004 and 2005 the pipelines were laid in a bypass around MCP-01, as they would still be in use to transport gas from other fields.

The Norwegian Frigg pipeline was tied back to the Heimdal gas hub, and became part of the Vesterled transport system. For its part, the UK pipeline was tied back to several fields on the British side. As a result, the pipelines from Frigg to St Fergus were not included in the cessation and removal work.

During the process, the possible use of Frigg installations as a hub for gas transport and processing was assessed. This requirement disappeared when Heimdal was converted for that purpose.

Before a decision was taken on removing the installations, detailed studies were prepared on the environmental consequences. These included a number of proposals for using the GBSs – such as artificial fish reefs, foundations for wind turbines or carbon-free gas-fired power stations, and foundations for a bridge across the Gands Fjord near Stavanger. Many of these options involved great technical uncertainties, and none were regarded as financially viable.

Possibilities for removing the concrete structures were also studied. Rimoval and disposal onshore was the first alternative that was studied. Under the 1998 Ospar convention, these could be left in situ if they were secured and satisfactorily marked. The GBSs had not been designed with an eye to their removal, and proved difficult to shift. Other alternatives of disposal were appraised as described in OSPAR decision 98/3. An accident while they were being refloated could have major consequences. The GBSs might collide and sink to the seabed in a damaged condition. Such a scenario would present a major safety hazard and high additional costs.

Cutting off the tops of the concrete shafts 55 metres below the sea surface was also considered. That would satisfy the IMO’s requirements, but was assessed to be even riskier than removal.

It was finally decided to abandon the GBSs and drill cuttings on the seabed. The latter are drilling residues which accumulate around a well. Surveys showed that the layer of cuttings on Frigg was thin and covered by sand. They derive from the topmost level of a well and contain no petroleum residues or polluting chemicals.

Steel jackets and all the platform topsides were to be removed, along with pipelines and cables on the seabed. By 2012, only the GBSs for the TP1, TCP2 and CDP1 platforms at Frigg will be showing above the water. They will be marked by beacons to prevent vessels colliding with them.

The goal is that 98 per cent of everything taken to land will be recycled.

Total E&P Norge awarded Stavanger-based Aker Kvaerner Offshore Partner AS a contract in October 2004 to serve as main contractor for the removal project and for disposal on land. The project included the installation at the Frigg field and the topsides of MCP-01. This job was worth NOK 3 billion, and a consortium comprising Aker Kvaerner Offshore Partner, Saipem, Shetland Decommissioning Company and Aker Stord were given responsibility for the work. Aker is to remove 85 000 tonnes of steel from 2005-08, of which 20 000 will be shipped to Shetland. The remaining 65 000 tonnes is being sent to Aker Stord for breaking up and recycling.

All pipelines were cleaned and every well plugged during 2004, and the platforms were also cleaned and readied for disassembly.

Removal work on Frigg got fully under way in August 2005, and is expected to continue until 2010. This work is being carried out module by module in the opposite sequence to their installation. The Saipem 7000 crane barge, which can lift up to 14 000 tonnes with its two cranes, has been used for the heaviest lifts. After being stowed on this vessel’s deck, the modules were transported to Aker Stord.

The process involved heavy module lifts combined with cutting the platforms up into smaller sections for transport in open containers to land. Saipem 7000 has worked on Frigg for a number of months, with more than 100 heavy lifts.

Plans call for the DP2 and QP jackets to be removed with the aid of buoyancy tanks. The structures will be raised gradually as the tanks are deballasted, and then towed to Stord for disassembly.

Because of earlier damage, the DP1 jacket cannot be removed in the same way as the others. The upper part of the DP1 jacket has already been cut off by a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) and removed by Saipem 7000. This work was coordinated by DeepOcean in cooperation with Norse Cutting & Abandonment AS. Using ROVs eliminated the need for diver assistance. Such vehicles have also been deployed for other cutting work on the various jacket legs. More than 1 200 such operations have been performed with the aid of ROVs. One of these units was also used to remove steel structures from the exterior of the TP1 and TCP2 GBSs.

Lifting of DP1

The heaviest lifts relate to TCP2 and DP1, with M35 as the heaviest module at 3 125 tonnes. Weighing some 9 000 tonnes, the module support frame for TCP2 is due to be raised in a single lift and shipped to Shetland. The DP1 topside weighed 3 700 tonnes.

To help coordinate this work, a dedicated website was established with information on the various installations. This Cessation Web site provides the various players with access to a digital library and has proved flexible and time-saving. Required information is posted for collective use within the project.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Mena: The Principles and Practice of Crisis Management. The Case of Brent Spar, London, 2006.

Creswell, Jeremy: Tackling Frigg – The Most Ambitious North Sea Decommissioning Project Yet. Aker Kværner Solutions, no 2, 2005.

Decommissioning Offshore Oil and Gas Installations: Finding the Right Balance, a Discussion Paper, E&P Forum, 1995.

Det Norske Veritas: Håndbok i konsekvensutredning ved offshore avvikling. Report no 00-4041, 2001.

Ersland, Bjørn Arild Hansen: 10 år – og verneverdig?, Norsk Oljemuseums årbok 1994, pp 47-57.

Grutle, Magnus: External steel removal for Frigg field platform, Scandinavian Oil-Gas Magazine no 1/2, 2007.

Hansen, Christian: From a Chinese butterfly to nails. Paper at the 23rd World Gas Conference, Amsterdam, 2006.

International Association for Oil and Gas Producers (OGP): Disposal of disused offshore concrete gravity platforms in the Ospar maritime area, Report no 338, February 2003.

Kongsnes, Ellen: Frigg field – the start of the new decommissioning era in the North Sea, (DNV) Oil and Gas News no 3, 2004.

Midttun, Øyvind: Pilot for a new era, Norwegian Petroleum Diary, no 2, 2002, pp 36-37.

Osmundsen, Petter and Tveterås, Ragnar: Decommissioning of petroleum installations – major policy issues. Energy Policy no 31, 2004.

Owen, Paula and Rice, Tony: Decommissioning the Brent Spar, London, 1999.

TotalFinaElf Exploration Norge AS: Frigg Field Concrete Substructures. An Assessment of Proposals for the Disposal of the Concrete Substructures of Disused Frigg Field Installations TCP2, CDP1 and TP1, Stavanger, 2002.

TotalFinaElf Exploration Norge AS: Frigg Field Cessation Plan, Stavanger, 2001.

Total E&P Norge AS: Frigg Field Cessation Plan, Stavanger, 2003.

Storting (parliamentary) documents

NOU 1993, 25: Avslutning av petroleumsproduksjon – fremtidig disponering av innretninger.

Proposition no 36 to the Storting (1994-95): Om disponering av innretningane på Nordaust Frigg og sal av statlege eigardelar i Smørbukk og Smørbukk sør: Recommendation from the Ministry of Industry and Energy, 31 March 1995, approved by Council of State on the same day.

Proposition no 50 to the Storting (1995-96): Olje- og gassvirksomhet, utbygging og drift av Åsgardfeltet samt disponering av innretningene på Odinfeltet.

Proposition no 8 to the Storting (1998-99): Utbygging av Huldra, SDØE-deltakelse i Vestprosess, kostnadsutviklingen for Åsgard m.v, og diverse disponeringssaker.

Proposition no 38 to the Storting (2003-2004): Disponering av betongunderstellet TCP2 på Friggfeltet. Recommendation from the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, 9 January 2004, approved by Council of State on the same day.

567jl is cool, plain and simple. It does what it says and is a solid option overall. I personally like the interface. Check it out and see if it’s for you! 567jl

U7777gameapk, been having some real good luck lately! Solid selection of games and the site runs smooth as butter. Check it out if you’re looking for something new. u7777gameapk

MCW7733 is cool. Easy to navigate and loads of games. Could improve on the bonuses, but overall a solid site. mcw7733